It was with sadness that I switched on the radio last week to learn of

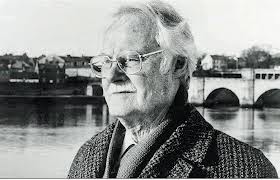

the death of Eric Lomax at the age of 93.

It was with sadness that I switched on the radio last week to learn of

the death of Eric Lomax at the age of 93.His remarkably powerful book, The Railwayman was excruciatingly hard to read in places, and must have been even more painful for Lomax to have written.

It charts his harrowing experiences as a Japanese prisoner of war in

1942. Captured in Singapore, he was a prisoner at the Kanchaanaburi camp in

Thailand. Here guards were to discover Lomax's homemade radio for which he and

his cell mates were subjected to the most horrific torture. During these nightmare episodes his English speaking interpreter would

repeatedly demand that he confess to espionage. But knowing that if he did he'd

be summarily executed, he remained steadfast.

Like so many victims of torture, Lomax's experiences haunted him in later life and eventually contributed to the break-up of his marriage. It was only after remarrying in 1983 that he was to get help from the then newly formed Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture. And it was here that he came across a press cutting from the Japan Times that told of an ex-Japanese soldier's quest to help the Allies locate the graves of their dead; a task for which he claimed he had earned their forgiveness. To Lomax's astonishment, the ex-soldier in question was none other than Takashi Nagase, the interpreter who had presided during his torture sessions all those years ago. For the next two years Lomax carried this crumpled piece of paper around with him but did nothing until he eventually acquired a translation of Nagase's memoir in which his former interrogator explained how shame had led him to build a Buddhist shrine beside the infamous 418 mile railway line to Burma built by Allied slave labour. And only then it was Lomax's wife Patti who contacted Nagase. "How", she asked, "can you feel 'forgiven' if this particular Far Eastern prisoner-of-war has not yet forgiven you?" It was enough to bring the two men together after more than half a century. For the remainder of their lives these two men were to forge the closest of friendships.

In 1996, Lomax published his memoir entitled The Railwayman. The film based on the book is due for release next year with Colin

Firth in the title role.

Eric Lomax was born on May 30 1919 and died on October 8 2011. He is survived

by a son and daughter.

Alex Pearl is author of Sleeping with the Blackbirds

Alex Pearl is author of Sleeping with the Blackbirds